Galápagos - the name takes me back to treasured childhood memories of watching documentaries about this archipelago, marveling at the wonders of untouched nature with my parents. Based on these memories and seemingly confirmed by biology lessons later on, I was somewhat convinced that only Sir David Attenborough could possibly be allowed to set foot on the pristine beaches of these islands. The thought that anyone could visit, board a ship to explore Galápagos, never occurred to me and the invitation to do so confused me for a moment before utter excitement took hold of me. My thoughts turned into a swirl of exotic creatures, gigantic tortoises, swimming dragons, colourful birds, khakis and Darwin’s theory presented in his book ‘On the Origin of Species’.

I learned quickly that while a lot is being done to preserve the uniquely untouched ecosystems of the Galápagos, it also is a place where people live, tourists are welcome and airplanes can land. Coming in, your luggage needs to be free of any invasive species (think seeds within soil under your hiking boots) that might contaminate the environment. Leaving the region, all luggage is being screened again - to make sure that not a single sea shell, coral, or bone is taken away.

Within the shortest time after landing on Baltra and taking a little boat across to Santa Cruz, we are driving on winding red dirt roads through lush highlands, already spotting the first species of the famous “Galápagos BIG 15“. Giant tortoises are roaming the very same roads as we are. Meeting these ancient reptiles is quite otherworldly. We admire the patterns of their skin, scales and shell, observe the snakelike faces, their beaks munching on grass. The steady foraging and inching forwards of these giants is how we learn that keeping the required 2m distance from all wildlife on Galápagos can be a challenge. The rule is in place to protect the animals, however they mostly disrespect it. They are not scared of humans, some are curious, some playful, some stoically carry on in their paths not caring whether they’re on a collision course with you or not. It’s your responsibility to make sure that you do not collide, but respectfully keep your distance to protect the wildlife here, backing off while keeping in mind that the closest creature might be behind you.

Santa Cruz is one of the 19 large volcanic islands in the Pacific Ocean that form the Galápagos Archipelago. Within a total of 127 islands, islets and rocks on both sides of the equator, this island has the largest human population in the region, all seven vegetation zones across its expanse, giant tortoises roam the misty highlands, sun-scorched Cerro Dragon is home to an impressive population of land iguanas, marine iguanas breed on the beaches and we’re heading to its largest coastal town. Outside Puerto Ayora, in a secluded bay with a public beach, iguanas, locals and guests of the Finch Bay alike enjoy the warm water and gentle waves of the ocean with white sand under their toes. The chirping of finches sound from the surrounding mangroves and tucked away in the green shade sits the small eco lodge Finch Bay, our expedition base for the next couple of days.

There’s a breeze going through the entire place, billowing the light curtains. The architecture respects and mimics the volcanic surrounding. No big volumes or iconic gestures, but clean, simple luxury around a peaceful cactus garden. Each room has an outdoor space with a hammock, no corridors but open walkways, natural materials and biodegradable soap and shampoo. The pool has an open-air bar and ocean view. The sunrise over the bay is glorious and serene, the coastal walk along a shallow bay with local residences, up to a long, deep, narrow gorge carved by a river you can dive into and along steep cliffs overlooking the ocean is worth every step before breakfast... before spending the day itself aboard a yacht. Leaving the big island to visit a small island, dive off the yacht into the ocean along the way, swim, snorkel, sunbathe, and discover the residents of another habitat, walk between prickly pear cactus and endemic “Palo Santo” trees alongside blue-footed boobies and accompanied by magnificent frigate birds swooping above.

Bartolomé Island, Pinnacle Rock

The Galápagos Islands are located some 1,000 km from the South American continent at the confluence of three ocean currents and have been formed by ongoing seismic and volcanic activity. The extreme isolation along with these processes have led to the development of an unusual plant and animal life, showcasing Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. The English naturalist visited in 1835 and noticed that marine iguanas, flightless cormorants, giant tortoises, huge cacti and various trees were not only endemic to this archipelago, but to specific islands within it - especially the many different subspecies of mockingbirds and finches - which inspired his concept of evolution by means of natural selection.

The designated wildlife sanctuary since 1935 and UNESCO World Heritage site of outstanding universal value since 1978 is an immense marine reserve, its landmass not only isolated from the rest of the dry world, but the islands within also so far spread that they form individual isolated ecosystems. The uninhabited islands are strictly controlled with carefully planned tourist itineraries limiting visitation.

During four days aboard the explorer vessel Santa Cruz II, we visit four uninhabited islands, crossing the longer distances in-between over night while being sound asleep in our beds. Visiting hours on those islands are after sunrise and before sunset, which is torture for photographers, limiting us to harsh daylight, but also protection for the wildlife - which is what this has to be all about - disturbing as little as possible, leaving no trace, being respectful and being in awe.

So each morning we wake up to a new place, to the undisturbed line of the horizon over the sea to one side, and the outline of an island to the other. Each of these islands is dramatically different from the one before, all of them under a clear blue sky, few with vegetation providing shade, plenty of them with beautiful beaches to land on, some with steps carved into a cliff face to climb onto a raised plateau, some flat as a pancake, others with hills, all of them habitat to astonishing creatures.

Whether just exploring the islands’ edges and cliffs from a little boat or kayak, snorkelling in clear waters just off shore or actually going on land, we are mostly greeted by playful sea lions. In small groups accompanied by expedition leaders is the only way to experience any of these places. Whilst protecting the wildlife by reminding anyone not to get to close, even though it’s tempting as the animals approach you without fear, making sure that everyone stays on the path and no one behind, these naturalist guides also have and share a wealth of knowledge about this unique place. So our little group of six photographers tried not to get our guide into trouble while learning the most from him, being quite the photographer himself.

On our first outing the expert guides us across Playa las Bachas on Santa Cruz Island to look for flamingos in the salt water lagoons. Following sea turtle tracks on the sandy beach without disturbing their nesting grounds, we see huge amounts of bright red Sally Lightfoot crabs on dark, volcanic rocks sticking up from the white sand full of bits of coral and shells. Next to marine iguanas, soaking up the sunlight while frequently blowing saltwater out of their noses, pelicans dive into the waves and rays glide through the clear water in plain sight from the beach - we are obviously in paradise.

Galápagos fur seal, Buccaneer's Cove, Santiago Island

The next day our guide takes us birdwatching on a little boat around Buccaneer's Cove. Santiago Island’s rugged and well-eroded coastline of tuff stone above a dark black lava flow is a geology lesson brought to life by fur seals resting in nooks, blue footed boobies, gulls and hawks perched on crannies and playful sea lions chasing our boat.

We land at Puerto Egas on a pitch black sand beach, welcomed by fur seals, their pups snoozing peacefully near the cliffs. On the short walk across to Sullivan Bay we get distracted from the amazing lava flow formations by a little flycatcher who seems interested in our cameras, landing on our hats, shoulders and lenses for closer inspection. We aren’t quite sure how to keep our distance and far too delighted to really care... Reaching the bay, the scenery is breathtaking. Black, volcanic rock formations, iguanas, urchins and crabs in rock pools and crevasses, sea water splashing through bigger holes connected to points beyond the tide line, natural arches connecting lava plateaus, seals playing in-between, calling each other and a graceful assembly of clouds rendering spectacular rays of sunlight across the moody sky. We hurry back to get off the island as the sun sets... with pockets full of sea urchin tests and spikes to be photographed on deck before heading to the next island.

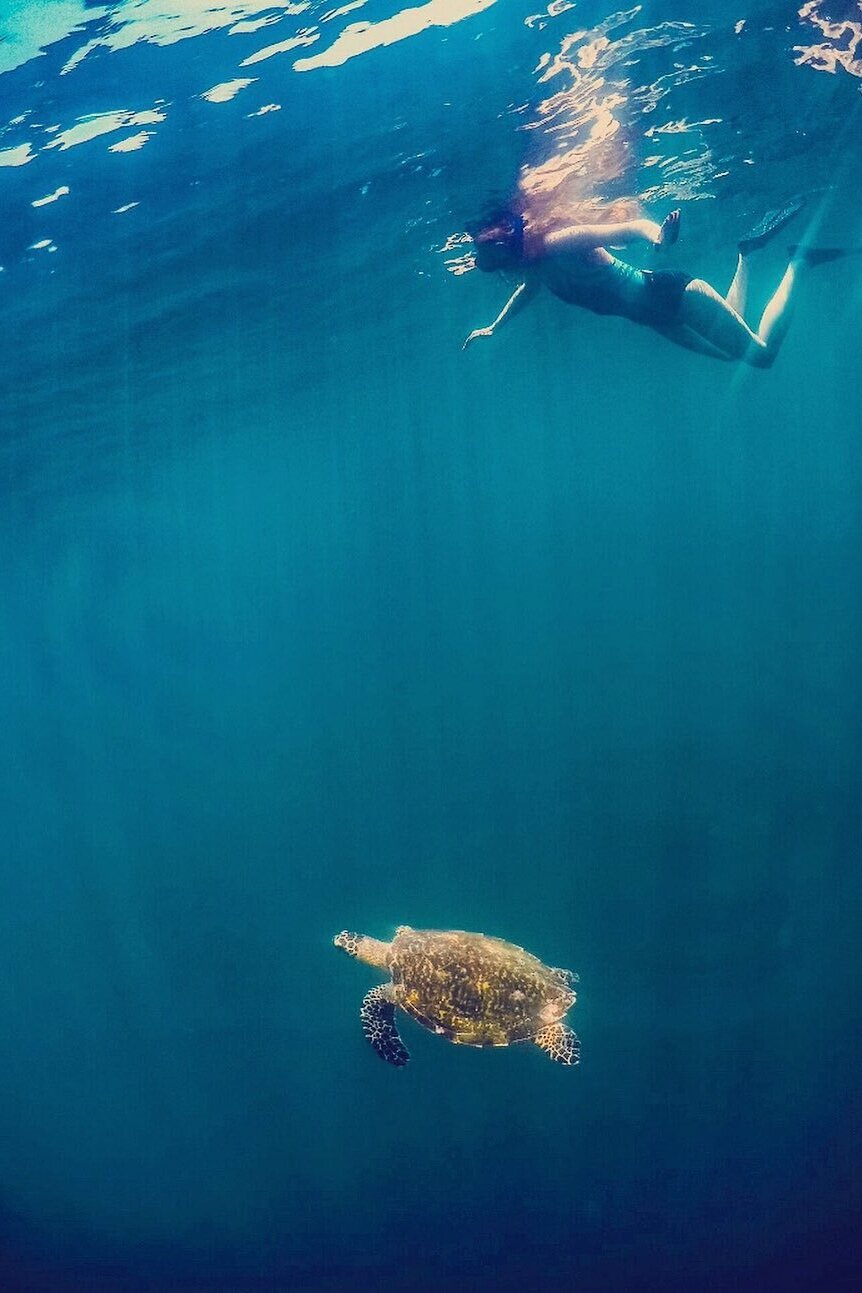

Rabida Island has stunning red beaches, green lakes and paths to high viewpoints across lush foliage and the deep blue sea. There’s excellent snorkeling around it. Swimming slowly alongside a sea turtle for quite a while, experiencing her rhythm of going up to breath and down again, the sunlight dancing, rippled by the little waves above, across the beautifully patterned legs and shell might have been my most magical experience of this journey.

After sailing over to the next stop, Bartolomé, and watching penguins from a little boat off Pinnacle Rock, we land on this rather small island with the most spectacular view in the archipelago. The landscape is young, hilly with volcanic cones and strewn with large rocks that can be picked up easily, as they weigh next to nothing, while following a wooden staircase all the way from the pier to a hilltop to take in that picture postcard view back towards Pinnacle Rock.

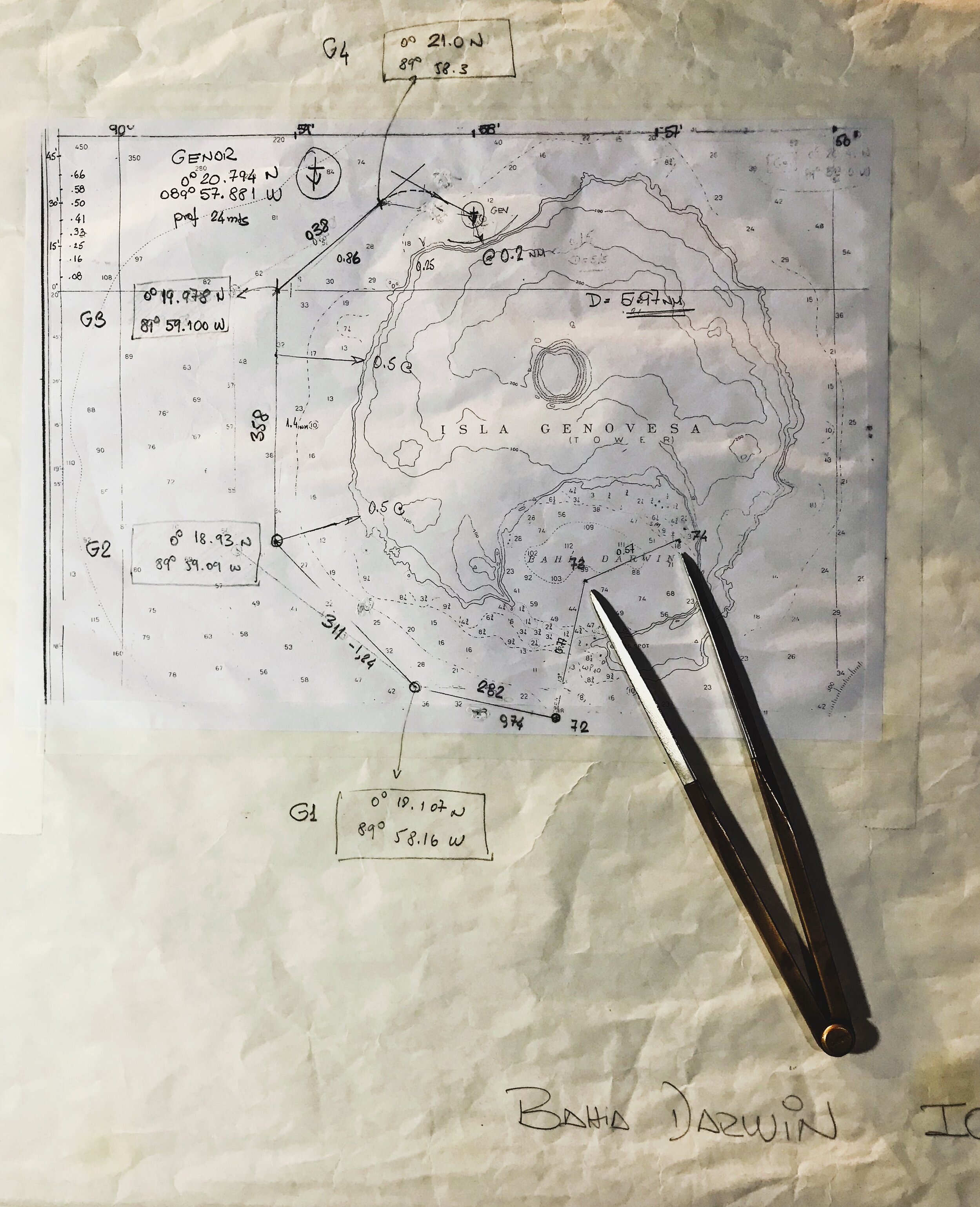

For sunrise of the last day, the captain invites us up on the bridge of the explorer vessel, to experience the navigation into the Great Darwin Bay of Genovesa. The island is made up of a volcanic caldera whose wall has collapsed, leaving a horseshoe-shaped plateau with steep cliffs surrounding the large bay. It is known as Bird Island, hosting nesting colonies of boobies (red-footed, blue-footed and Nazca), great frigate birds, short-eared owls, tropicbirds and many more. The place is so crowded by boobies nesting on the ground and in trees that we need to stay on high alert with every step we take to avoid walking into a bird, chick or egg - while the tropicbirds keep flying in endless loops over the shoreline, apparently never sitting still, presenting a more challenging subject for photographers.

The snorkelling in the bay gives the so far most complete insight into the underwater spectacle of the Galápagos Marine Reserve. Not only is the water teeming with abundant life forms ranging from corals to sharks to marine mammals, but the sea floor is close and the underwater geomorphological forms provide an amazing backdrop, rising above the surface to form cliffs, inhabited by more wildlife, dipping in occasionally. Sea lions keep us company, reef sharks swim just low enough to not be terrifying, we catch glimpses of spotted rays and occasionally schools of little silvery blurs surround us entirely, before we can carry on observing green-turquoise-pink parrotfish munching on corals, while yellow tails are swooshing past. There are countless beautiful fish species I can’t name all around us, starfish and urchins below, but our quest to spot a hammerhead shark remains unsuccessful. Most of the wildlife in the archipelago is so reliably found in the very spot the guide takes us to see it, that we’re almost a little confused by not being able to simply tick the particular type of shark we want to see off our list. Almost relieved I remember that we also didn’t get to see the flamingos on our first day of exploring - so it is wildlife after all. Sometimes it felt a little like visiting good natured zoo animals posing for our cameras - but no, it simply is a unique, remote area, where animals are plenty and do not identify humans as a threat.

After a last night of stargazing in the middle of the ocean, without any light pollution at all, in-between enchanted islands, protected by and from civilization, we return to the little airport on Baltra. Our luggage holds documentation, signed by the captain, confirming that we have crossed the equator on our expedition. It does not contain foraged or found mementos, as mine usually does. Every shell, feather, pebble or stick was collected by camera only and left behind. The straw hat, bought at the very same airport on our way in will keep reminding me of our time here, as I’m afraid the Galápagos coffee beans purchased on our way out won’t last long enough to proof that these islands really exist, with coffee as well as Palo Santo trees growing on some of them.

THE LOWDOWN

My trip was curated by Bird with Metropolitan Touring - Ecuador travel experts since 1953 and sponsored by Olympus.